Contents

-

How could the akiyas be turned into a property of Mom’s Co-op?

-

How could the gaps be turned into a property of Mom’s Co-op?

-

How could the edges be turned into a property of Mom’s Co-op?

-

How could the infill plots be turned into a property of Mom’s Co-op?

-

How could the underused public buildings be turned into a property of Mom’s Co-op?

- Organization

- Design prescriptions

- Fluid space, fluid sense of home

- Landscape as anchor

- User experience

SITUATION

A1

Where does this project start?

This all started with a group of single mothers living in Tokyo Internet cafes because of homelessness. They live with their children in small cubicles of 1m x 1.9m.

Although the space is cramped and crowded, it is still somehow a “cozy” home that these families live in when they have no other accessible choice.

A2

Ministry of Health, L. a. W. (2016). 平成28年度全国ひとり親世帯等調査結果報告. [厚生労働省]

NHK「女性の貧困」取材班. (2014). 女性たちの貧困 “ 新たな連鎖" の衝撃. Tokyo: Gentosha Literary Publication.

Who are the mothers?

According to the report from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, an average Japanese single mother family has two kids and a mother with a part-time job.

Due to the poor employment and income status of Japanese women, over 50% of single mother households are in poverty, which is the direct cause of housing poverty.

A3

How do we live in a place without anything homely?

Based on the available visual materials, the life of a single mother living in an internet cafe is unfolded in detail, representing her daily routines. A variety of media are combined: traditional Japanese prints are used to show the spatial structure; real photographs are collaged to represent signs and visual landscapes; and 3D model renderings are used to add important objects from her life.

A4

What is wrong with nuclear family housing in Japan?

Decades of research have identified domesticity as one of the specific ideological constructs of Western civilisation (Sand, 2005). Indeed, the idea that the intimate family is historically stable, universal, and natural has been systematically disproved by social historians since the publication of Philippe Aries's Centuries of Childhood (1962), which stated that the family as we know it today—a private, domestic circle founded upon mutual affection—is a relatively new concept (Ariès & Baldick, 1962).

A

B

C

Yamamoto. (2020). Doma In A Nagaya.

Giudici, M. S. (2018). Counter-planning from the kitchen: For a feminist critique of type. The Journal of Architecture, 23(7–8), 1203–1229.

cinq. (2018)

machiya

~1615

danchi

1945

share house

2018

← click to enlarge

Traditionally, there is no concept of nuclear family in Japan. Workers and masters shared a house. Spaces are also not gendered; both men and women can be seen working in the kitchen. and it is fluid between different spaces.

Post-war suburban housing helped introduce the Western concept of the nuclear family. The separate kitchen became a "mom" space. Mothers were isolated in a single nuclear family home, with little interaction with city life.

In response to high rents, shared housing is gradually emerging in large cities like Tokyo. In addition to each small family having their own bedroom, they share a kitchen and living room while sharing household chores such as cooking.

Shimokawabe, J. (1780). Onna-yō Chihiro Hama [The Woman’s Thousand-Fathom Shore]

(Kikuya Chobei).

Nikkei. (1960). The Realtor Introduces Danchi To A Nuclear Family.

The male servant and maids prepare meals together (Shimokawabe, 1780).

Mother work in the single family kitchen (Nikkei, 1960).

Shared meal and shared domestic labour in a share house.

Shinjuku, Tokyo

A5

Where are these happening?

Tokyo usually refers to Tokyo 23 Special Wards. This is the most prosperous area of the Greater Tokyo Area. Among the wards, Chiyoda, Chuo, and Minato together form the centre of Tokyo, which is the richest area of Tokyo in terms of transport, job, and education. Even the smallest 1R home (Usually between 13-sqm to 20-sqm in size) has the highest rents in the area. (Minato's monthly rent of ¥127,100 is

approximately £900)

Shinjuku is one of the busiest districts in Tokyo, located close to the city centre. Many subways pass through Shinjuku station. Kabukicho is the most important business district around Shinjuku station and is also where many internet cafes

that Tokyo's single mothers live in gather.

Kitashinjuku

Kitashinjuku residential area.

Franco, T., 2018. Kabukicho | Tokyo Red Light district. Available at: <http://www.timfranco.com/china/photographer/professional/shanghai/blog/2018/11/6/kabukicho-tokyo-red-light-district> [Accessed 29 May 2022].

The Fundamental Concepts state that the city Shinjuku aspires to be is:

A Peaceful, Bustling City Created with the Power of Shinjuku

Source: Shinjuku City, 2017

① Is there any planning policy that affects the design?

Japanese planning is relatively liberal in general.

There are few bulk and density controls, limited use segregation, and no regulatory distinction between apartments and single-family homes.

For instance, in Japanese zoning, cities can only define 12 different zones, going from low-rise residential zones to exclusively industrial zones.

Furthermore, liberal regulations mean they encourage mixed use even in an specific zone. An exclusively residential area (not actually exclusive as it allows small shops, clinics and services), is designed to ensure that buildings are not too large and to keep some functions out. A commercial district does not prohibit housing.

② What is Shinjuku typology?

Buildings & Blocks

Shinjuku has a wide variety of building types, but the biggest thing they have in common is: a small footprint.

pet building

building facing street

building facing

main road

iconic building

blcok

building type

restaurant / tea house / information centre

program

restaurant / sex shop / chess room / internet cafe

restaurant / cafe / convenience store

hotel / cinema / shopping mall / game centre / internet cafe

Objects & Material

iconic object

billboard

road

light

material

A6

What are the pros and cons of emerging share houses in Tokyo?

A new form of living known as the share house (shea hausu) developed at the turn of the millennium, first in Tokyo and then in other large cities, reintroducing community life as a critique of isolated living (Druta & Ronald, 2021). A lightly furnished private bedroom and a set of communal amenities make up a share house life; it is a highly commodified type of communal living. Typically, a share house has a communal living room, a shared kitchen and dining area, and a bathroom with a shower and toilet.

This section analyses existing share houses and discusses what spatially allows sharing to happen, how such houses can be a home without anything homely, and the limitations of current share houses.

open shared kitchen

spatially adjustable

mixed-use

layers and transparency

multifunctional shared space

flexible individual space

let nature in

Pros

limited access to shared space

underused public space

vague boundary of

personal items

lack of bathing space

hard to find

low quality children space

sense of being organised

Cons

PRECEDENTS

B1

How is live-work planning and design?

Integrating work and life in the same or adjacent spaces is one way to resolve the work-parenting conflict for single mothers, instead of clear zoning.

Thomas Dolan designed what is said to be the first new-construction live-work community in the US since the Great Depression. It was called South Prescott Village, and it struck a blow at the American fixation on separating the workplace from the home.

In Live-Work Planning and Design: Zero-Commute Housing, Thomas Dolan presents three prototypes of live-work.

LIVE WITH

This type of space is what most people imagine when they picture a typical live-work space. A live/with unit is typically a single space, including a kitchen located below a mezzanine/sleeping space, which looks out over a large contiguous working space. The amount of space devoted to the “live” area and the “work” area depends on the occupant’s needs at the moment, and will likely vary over time as a result.

LIVE-NEAR

Live-Near™ meets the needs of those who feel that the proximity afforded by live/work is important, but who would nevertheless would like some separation between living and working spaces. This can be to minimize exposure to hazardous materials or high-impact work activity, out of consideration for family or roommate, or simply to fill the need for the bit of distance created by a wall or floor.

LIVE-NEARBY

In this configuration, a short walk separates the living portion and the work space– across a courtyard, to a converted garage or other accessory structure, or up or down an exterior staircase, for example. While this type may initially appear to be simply mixed use, classification as live/work may permit its existence in places where a residential or a commercial space alone might not be permitted.

“The potential market for live-work consists not only of people who currently work at home full-time, or even those who work at home part of the time, but also those who would work at home if only their home could accommodate work”

— Zimmerman and Volk

B2

How do we generate new space in a high-density area?

Tōkyō Kōgyō Daigaku. Kenchiku Gakka. Tsukamoto Kenkyūshitsu, & Atorie Wan. (2001). Petto ākitekuchā gaidobukku = Pet architecture guide book (World mook series ; 327). Tokyo: World Photo Press.

Japan's metropolitan areas are full of these ready-made examples. The Pet Architecture Guidebook from Atelier Bow-Wow collected together examples of what they interpreted as new types of uniquely Japanese metropolitan vernacular architecture. Micro buildings are squeezed into gaps between larger buildings, or on minuscule plots.

These strange curiosities are at once ridiculous and highly functional. This is the forgotten architecture of Japan – an extreme design realisation of the pragmatic philosophy that underpins popular Japanese design.

“The Japanese seek to maximise the potential of small spaces to their extreme.”

B3

How can people with low income find a place to live in Tokyo?

由井義通, & 矢野桂司. (2000). 東京都におけるひとり親世帯の住宅問題. 地理科学, 55(2), 77-98.

Ronald, R., & Nakano, L. (2013). Single women and housing choices in urban Japan. Gender, Place & Culture, 20(4), 451-469.

The spectrum of general accessibility of different housing choices for single-mother families is as follows:

① natal home

② capsule-like rental dwellings, eg. internet cafe

③ mother and children housing facilities

④ shared living in the private rental sector

⑤ public housing (including Toei Jūtaku, which is also called Danchi in the post-war time)

⑥ private rental sector

⑦ homeowning

Considering that poverty among single mothers is associated with less family support, this study is to focus on four of these relatively affordable housing options.

A

capsule-like rental dwellings

The internet cafe cubicle is the minimal living space for the one who is unable to find housing.

B

mother and children housing facilities

The mother and children housing facilities were established under the Child Welfare Act to protect non-spouse mothers and children and to support their lives in order to promote independence.

An assessment is required to move in. Only a minimal amount of rent is required.

However, the number of facilities nationwide is not sufficient to support all mothers in need.

C

shared living in the private rental sector

The codona HAUS project is a share house for single mothers operated by a NPO.

D

public housing

Danchi is a large cluster of apartment buildings or houses of a particular style and design, typically built as public housing by government authorities.

Danchi is designed for the Japanese salaryman life around the nuclear family in contrast with the multi-generation homes before the war.

Rent is cheap, but a lottery is required to obtain it.

TOOLS

Diverse options are used to explore possible approaches. The three parallel proposals originated from three different scales and evolved into a matrix. The final goal is to create a supportive community for single mothers to live together, providing quality, efficiency, safety, positive cycle, and identity.

I

What if Shinjuku is surrounded by single mothers’ housing?

II

What if 10% of each commercial building is operated by single mothers?

III

What if housework is counted as labour?

Shinjuku Ribbon

a top-down proposal from the perspective of the city which ultimately forms a megastructure

10%

at medium scale, starting from a typical block in Kabukicho in Shinjuku, generating changes from one simple policy

Domestic Labour

from the view of tiny, intimate spaces and develops in a bottom-up way

Film & TV Works:

Araki, I. (2020). 3人のシングルマザー.

Ayuko Tsukahara, Kentaro Takemura, Ryosuke Fukuda,

& Yoshiaki Murao. (2015). Mother Game.

Fukuda, R., & Murao, Y. (2021). Kazoku Boshu Shimasu.

Kazutaka Watanabe. (2021). Only Yesterday.

Mizuta, N. (2013). Woman.

Takahisa, Z. (2021). Tomorrow’s Dinner Table.

C2

What are the things of home?

Home is made of matter. But when architects try to build a home out of objective items it would be difficult, because the atmosphere of the home is also made up of everyday bodily experiences. In order to create a better feeling of the home, we need to try to describe the real atmosphere: what is it like to feel at home?

← an important sign of home: eating together

Activities of Home:

Togetherness vs. Detachment

The lived experience of intimate atmospheres is shaped within the dynamic interplay between the involvement in, and detachment from, sociality (Daniels, 2015). This entanglement of togetherness and detachment is mainly reflected in daily activities, such as eating, sleeping, bathing, and resting.

|

|---|

|

|

|

Layers of Home:

Inside vs. Outside

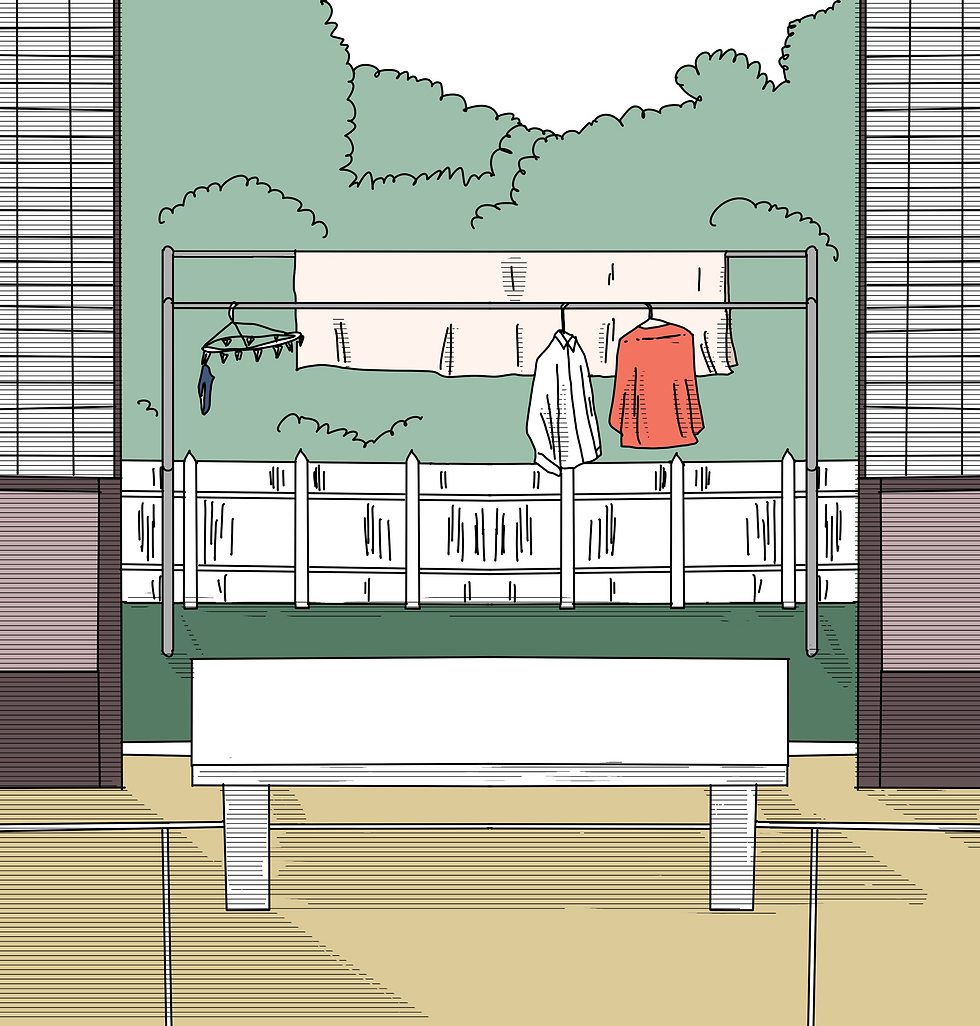

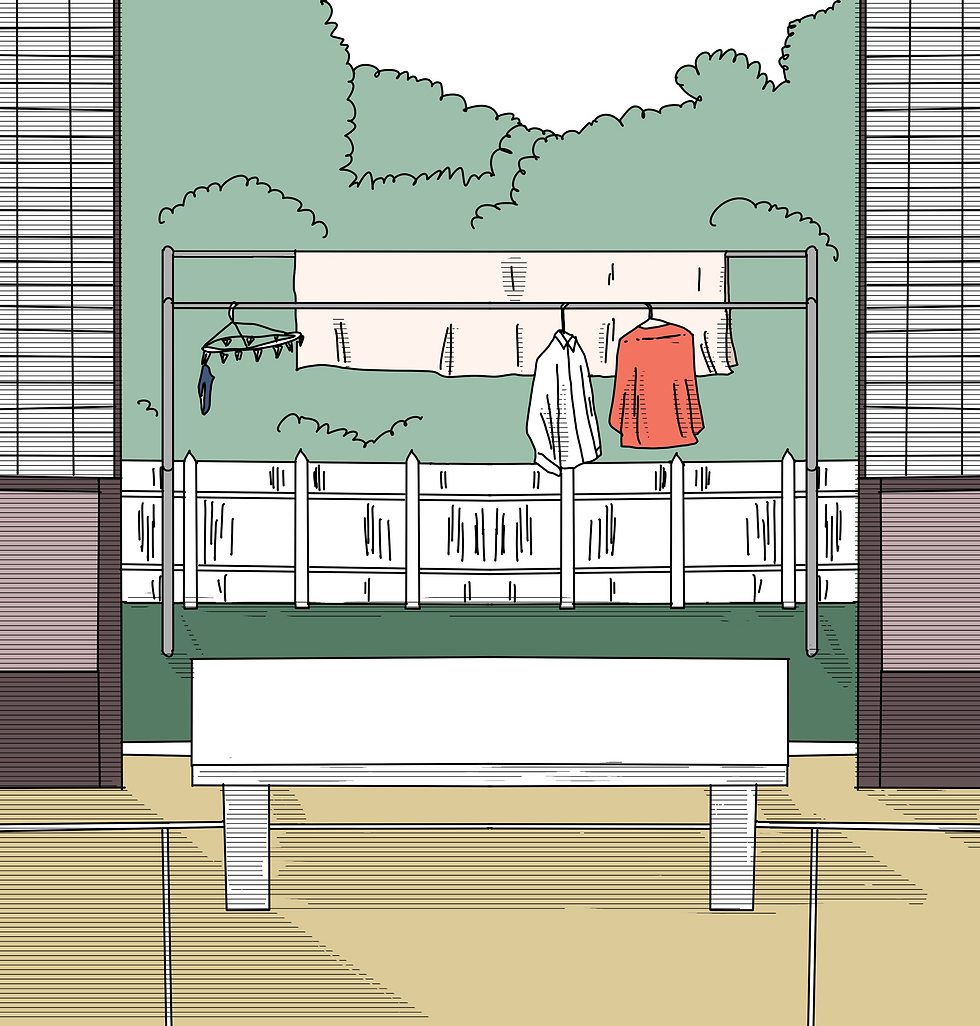

Japanese homes often have layers of physical barriers to protect the inside (Uchi) world from the outside (soto) (Ozaki & Lewis, 2006). However, the inside-outside boundaries of the home are fluid.

Objects of Home:

Display vs. Storage

Objects and storage have always been a high priority in Japanese home life, which is part of the material culture of Japan. Numerous studies have shown that a typical Japanese home will have a small number of items deliberately chosen for display and a large number of useful or useless items stored away (Cwerner & Metcalfe, 2003).

DISPLAY

STORAGE

C3

What do objects in a world designed for single mothers look like?

In order to design a world in which single mothers can live with dignity and quality, I developed a range of objects as props to explore the qualities that this world should have.

① Things for single mothers

The initial idea of the co-operative was to collaborate everything in life and work in order to reduce the responsibilities that one single mother needs to take on alone.

The three most important forms of cooperation are: co-parenting, co-living, co-working.

Cooperation will be reflected in material objects.

Cooperation and socialized motherhood are starting points of a feminist society.

② How should the city accommodate females

When designing for women, gaining equality by rebelling against male authority is an important path. For example, new subway seats here are designed to protest against manspreading; or infrastructure to keep women safe in the face of male violence or harassment.

subway seats to prevent manspreading. the majority of women use public transportation, but the majority of area of seats on public transportation is always occupied by men

the emergency uncomfortable/unsafe button can be seen everywhere on the street. When pressed, members of co-op in the surrounding area will receive a prompt to move closer to this area to improve crowd density and thus improve safety

when feeling the mansplaining, silence him as extinguishing the fire

distribute period pain tablets gashapon machine as part of the city's infrastructure at a very low price

C4

What space do we share?

Femininity is an inclusive temperament. So a city designed for women, designed for mothers should be a city that is friendly to everyone.

This city would have no specific boundaries or functional zoning, which is a product of a patriarchal society. Instead, this is about to be a positive, shared, and supportive city.

← click to enlarge

eat bento alone → prepare bento together

do daily shopping while taking care of children

→ one mother takes care of everyone's children in the children's corner

each one takes care of their own children → one person takes care of everyone's children

buy snacks as meals on a vending machine → co-sourcing for lower prices, distribute at the dispense point

work in the bento store on the 5th floor → operate a bento store together on the ground floor

C5

Test 01

As a summary of the exploration of design tools, three moments were developed. They show how shared, fluid, ambiguous spaces can help single mothers inhabit the city and support each other.

Current view of Kabukicho 1 Chome Rd.

CREATING THE IDENTITY

D1

What is the Mom's Co-operative?

Mom's Co-operative organises and leads a community of moms. Helping moms join this organisation in Kabukicho, Shinjuku, to gradually improve their living environment by living and working together. Providing support and training, it helps mothers to leave the crowded accommodation in Shinjuku and move on to a wider world.

In order to obtain start-up funding, Home Shinjuku was combined with the government's Community based Integrated Care System (CICS). Financial and human support is obtained through the renovation, occupation and upgrading of existing local businesses as a care node.

D2

How could we find a place for home in Shinjuku?

Through its disparate and dispersed layout, House Shinjuku seeks to give women and children a flexible home that is closely connected to the urban context. By breaking down prescribed roles, prescribed functional zoning, and even prescribed hourly schedules, it seeks to create an encouraging and supportive environment.

The diversity of spaces should accommodate various requirements and the differing interests of single mothers according to their lifestyles, encouraging more families to choose to join this supportive community.

In order to be able to find places where such a supportive network could be laid in a built-up city centre like Shinjuku, the types of space that could be developed were identified.

Through fieldwork and literature research, five site types were identified as having the potential to serve as the basis for design guidelines.

D3

What is the architectural identity of Mom's Co-op?

Since the mainstream nuclear family housing, and indeed the mainstream city, cannot accommodate single mother families, we need to create our own architectural identity. Making it easier for single mothers to get a better quality of life.

I / Afuredashi

Considering the accessibility issues in the current shared house public space, this project suggests the creation of a non-defined space that is not privately owned. However, it enables long-term private occupation, fostering informal communication and mutual assistance.

akiyas

typical site 1

gaps

typical site 2

edges

typical site 3

infills

typical site 4

underused

typical site 5

II / Mixing

Live-near-work is a critical feature in every property of this project that enables single mothers to perform their double role of working and parenting.

akiyas

typical site 1

gaps

typical site 2

edges

typical site 3

infills

typical site 4

underused

typical site 5

III / Adding

In order to optimize the spatial experience of single mothers, the project took the form of attaching new structures to existing ones to create a spatial surplus, considering the limitations of the available open space in Tokyo and the available initial funding.

akiyas

typical site 1

gaps

typical site 2

edges

typical site 3

infills

typical site 4

underused

typical site 5

Turn the traditional living room into non-defined space

How can we build fluidity in ‘ home’ with light-weighted structures?

How do we add? As this project is about providing the best "home" solution with limited funds, the price of materials, the ease of installation, transport and maintenance need to be taken into account. The final decision was to use lightweight timber construction.

pine wood |  light oak |

|---|---|

glass printing |  japanese paper |

timber |  grass |

fabric |  polycarbonate |

gravel |  shoji |

fabric |  futon |

tatami |

APPLICATION

Tests on typical sites

Having established the architectural identity of the single mothers, this series of unifying principles was applied to five typical lots. A typical solution is provided to make these architectural designs more easily replicable, creating a larger community scale.

ADAPTATION

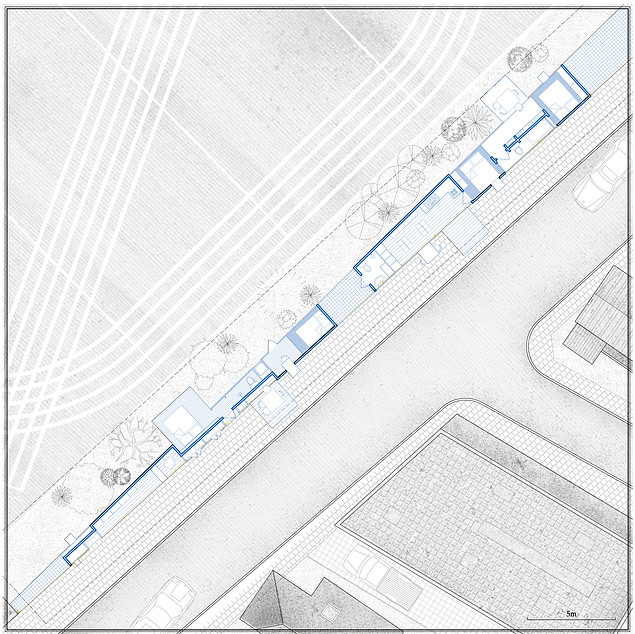

The adaptation of the above guidelines for a typical lot to a real site requires a simple teaching. This case study serves this purpose.

The real site is located at the edge of Shinjuku City Riyodobashi No. 4 Elementary School. The block is bounded on three sides by the school building and on one side by a fence.

The proposal is to widen the fence and use it as a home for three to four single mother families. They will jointly operate a kiosk within this structure as a source of living expenses. The school-age children would just be able to attend primary school nearby.

F1 / Objects & Material

F2 / Design prescriptions

← click to enlarge

A series of restrictions were attached and they were applied when the lot was replaced. Some of these were to not affect the use of existing urban space, for example by leaving a minimum of 2m pavement. Others were to create a unique spatial experience, such as a sloping roof that gives a different atmosphere to the public-facing and school-facing sides.

The large number of variable structures allows the 'home' to change shape to suit different needs.

← click to enlarge

F3 / Fluid space, fluid sense of home

The definition of space is fluid, as is the scope of the home, due to the presence of variable structures. The same users can also change the structure to achieve the optimum level of air flow and light.

F4 / Landscape as anchor

There is an open space on the side towards the school. The landscape on it serves both as a garden for mum and the children and as a threshold between the school and the private house.

F5 / User experience

The guidelines for this project and the way they are applied will be updated and iterated based on the feedback received from users. It is hoped that a building system will be constructed that will satisfy most single mothers.

With limited base conditions and funds, it may be that this own room is not very large. But it is rather more like a 'home' than living in an internet cafe or share house.

It's not about how big the room is, it's about how much control we can have over our lives.

Shinjuku City Riyodobashi No. 4 Elementary School

This is not an affordable housing.

It's about how a group of women who are not socially and culturally accepted

can occupy and enjoy the city

on their own.

""

G

Additional Work

Contact Us

Address

〒169-0074 Tokyo, Shinjuku City, Kitashinjuku, 1 Chome−9−10

グランヴィル北新宿